How is this possible? Well, because quantum particles are not really just particles. Rather it is delayed until the particle is well past the slits, on the way towards the far field. We saw what others have missed because this velocity disturbance doesn’t happen as the particle goes through the measurement device. We don’t have to get into what they claimed was the mechanism for destroying interference, because our experiment has shown there is an effect on the velocity of the particle, of just the size Heisenberg predicted. Hence, they argued, it is not Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle that explains the loss of interference, but some other mechanism. Any measurement that gives different results depending on which slit the particle goes through will do.Īnd they came up with a device whose effect on the particle is not that of a random velocity kick as it goes through. What the eminent quantum physicists realised is that finding out which slit the particle goes through doesn’t require a position measurement as such. We know the answer is no, and Heisenberg’s explanation was that if the position measurement is accurate enough to tell which slit the particle goes through, it will give a random disturbance to its velocity just large enough to affect where it ends up in the far field, and thus wash out the ripples of interference. Wikimedia/NekoJaNekoJa/Johannes Kalliauer, CC BY-SAīut what if we put a measuring device near the barrier to find out which slit the particle goes through? Will we still see the interference pattern? There are bands (dark) where they are more likely to show up separated by bands (light) where they are less likely to show up. Particles going through two slits at once form an interference pattern on a screen in the far field. The signature of this is the so-called “interference pattern”: ripples in the distribution of where the particle is likely to be found at a screen in the far field beyond the slits, meaning a long way (often several metres) past the slits. Since we can’t know which slit the particle goes through, it acts as if it goes through both slits. We also have a quantum particle with a position uncertainty large enough to cover both slits if it is fired at the barrier.

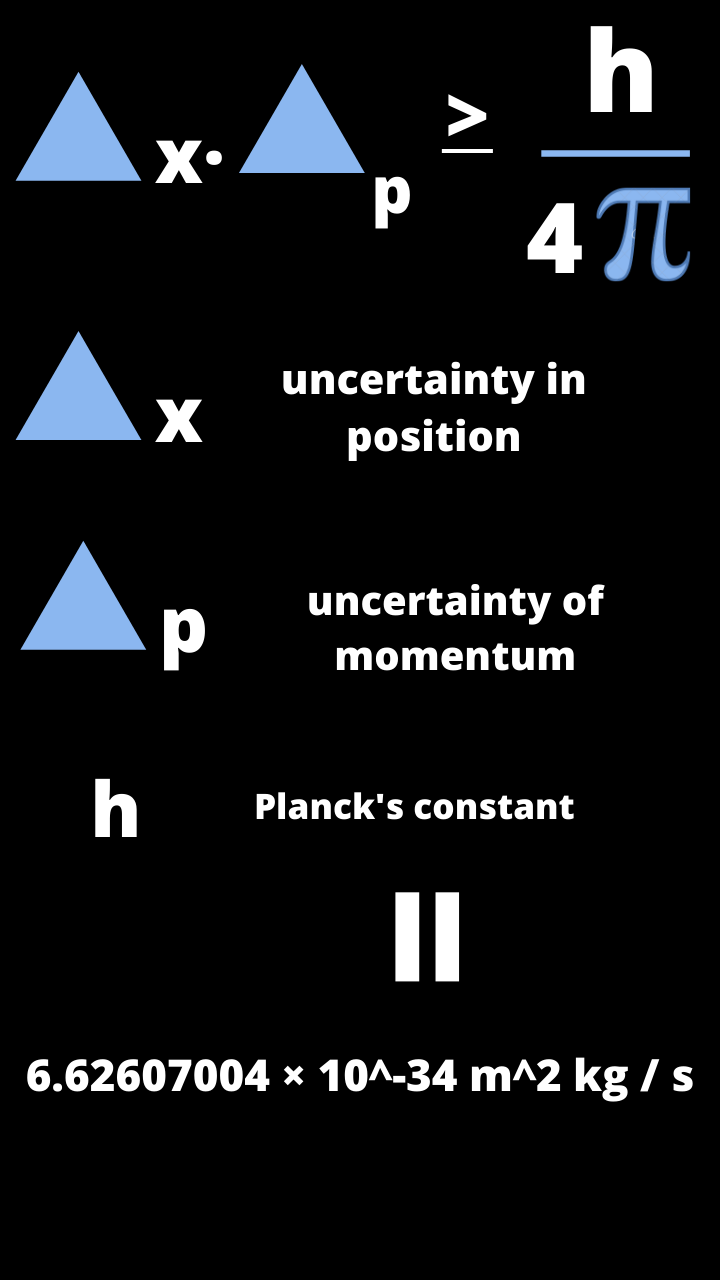

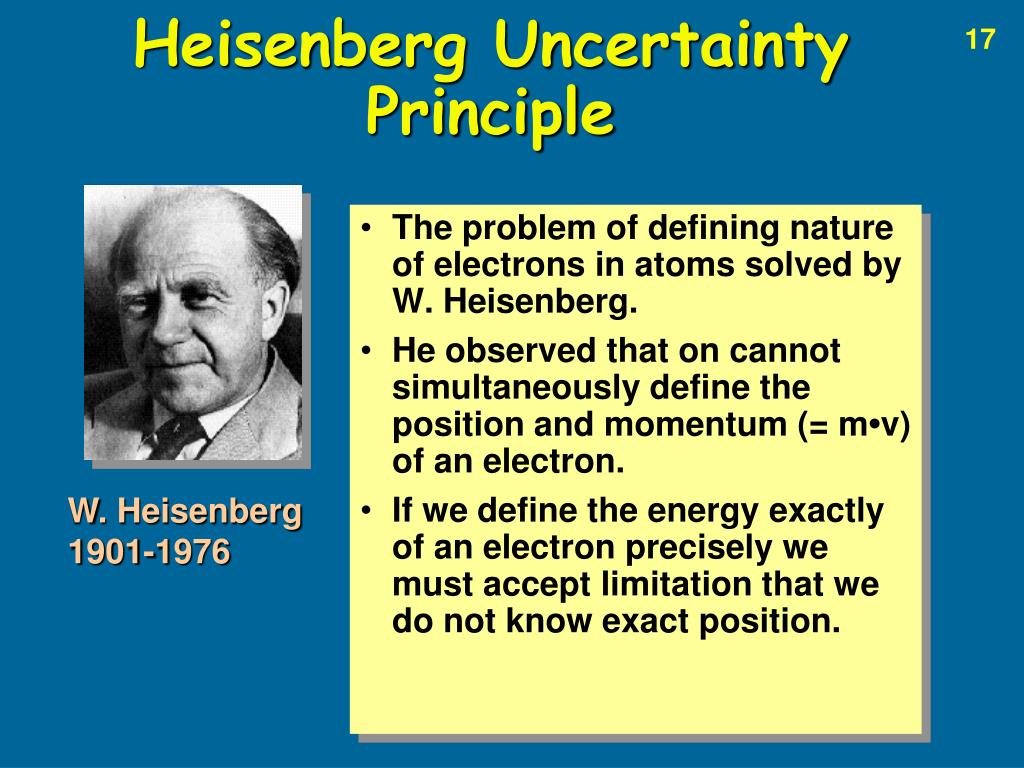

In this type of experiment there is a barrier with two holes or slits. We show a velocity disturbance - of the size expected from the Uncertainty Principle - always exists, in a certain sense.īut before getting into the details we need to explain briefly about the two-slit experiment. Heisenberg used the Uncertainty Principle to explain how measurement would destroy that classic feature of quantum mechanics, the two-slit interference pattern (more on this below).īut back in the 1990s, some eminent quantum physicists claimed to have proved it is possible to determine which of the two slits a particle goes through, without significantly disturbing its velocity.ĭoes that mean Heisenberg’s explanation must be wrong? In work just published in Science Advances, my experimental colleagues and I have shown that it would be unwise to jump to that conclusion. But this measurement would necessarily disturb its velocity, by an amount inversely proportional to the accuracy of the position measurement. For example, measuring the particle’s position would allow us to know its position.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)